Prof Daniel Chua on Music for Hope and Healing

Note: In this transcript of their dialogue, Professor Sri Sreenivasan is informally identified as Sree and Professor Daniel Chua is Daniel; the transcript has been edited for readability and length.

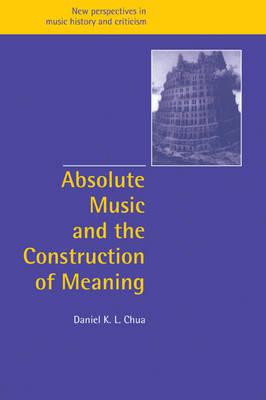

Sree: Welcome to another in our live global conversations about the COVID-19 pandemic. Today we’ll be talking with Professor Daniel Chua about how music can help us cope. Professor Chua is Chair Professor of Music and the Mr. and Mrs. Hung Hing Ying Professor in the arts at the University of Hong Kong. He’s also president of the International Musicological Society, an association of researchers in all aspects of music. He earned his PhD in musicology at Cambridge University, and has taught and conducted research at many institutions around the world, including Cambridge, King’s College London, Yale, and Harvard. He is particularly known for his work on Beethoven, and the intersection between music, philosophy, and theology. HIs books include Beethoven and Freedom, Absolute Music and the Construction of Meaning, and The Galitzin Quartets of Beethoven.

Professor, what is the power of classical music? How do we make it relevant in today’s age?

MUSIC AS TIME TRAVEL

Daniel: Well, all music is powerful, not just classical music, but I happen to work mostly on classical music. For me, classical music is really about what music can speak to over long distances of time. You know, the idea of classical is something that, if I were to ask “Beethoven, do you write classical music?” He would say, “Well, what are you talking about?” Because in his day, he was just writing modern music. So classical music is a retrospective term. It’s a way of saying, look, we’re all modern people, we’re all up to date, we all live according to fashion, according to trends, but what can outlast all these trends? What can outlast fashion? So we coined this term “classical” to speak of music that can speak despite all the changes that happen over time. They still speak to us today.

For me, classical music is always relevant because it carries these very big existential questions with it. When I listen to classical music, often it’s a kind of time travel, back to the time of, say, (Austrian composer Joseph) Haydn. I’m listening to his music, his time. Of course, nobody would write that kind of music today. But when I listen to the music of the past, suddenly it speaks to the present in some ways.

Classical music is relevant, because it teaches us to listen to the past, it teaches us to listen to the very big questions about life, and it teaches us to listen to difference, because music is different from us now. This is music of a long time ago, so it’s not now and it’s not about me. This is what classical music does: it teaches us to listen to music carefully.

Sree: I love how you described yourself talking to Beethoven. People who are scholars of great creators of the past are always in dialogue with the people they study. Just as you talk with Beethoven, people who study Shakespeare are always talking with Shakespeare. I also like the idea that if you asked him, Beethoven about it, he would say, “I’m creating music.” We joke that in India, people don’t say, “I’m going to have Indian food.” We just say, “We’re going to have food,” right? You used the word musicology. Can you describe what that means?

Daniel: Musicology is the study of music. It’s the study of any music in any way that you want. So it could be historical, it could be anthropological, or ethnographical. It could be from a psychological perspective or philosophical or theological one. Whatever you want, really. So I classify a musicologist as anybody who studies music in a scholarly way.

Sree: Do you distinguish between kinds of music? In the international musicological association you lead, do you have different subsections or interest groups or chapters?

Daniel: We do have different interest groups and so on, but my emphasis has been on the idea that everywhere music is music, and we should treat all types equally. So it’s not just about Western music, or classical music or this method or that method. All music counts because all music is very interesting to think about and to talk about, and we need to have open borders when we do our kind of research rather than closed borders. Music should open out the world and not close it in.

Sree: That’s a very good point for us to think about today because there’s so much pain people are going through. Okay, for those just joining us, we’re talking with Professor Daniel Chua of Hong Kong University, who also is the president of a global association of researchers in all aspects of music. Professor, how often do you get together for conventions and conferences?

Daniel: We have one big party every five years. We move at a glacial pace. But of course, nothing really happened this year because of the pandemic so we’ve just had all kinds of Zoom gatherings. But when we get together, we have a lot of fun. Of course, we’re musicians and musicologists. We always have a great time.

Sree: You must have amazing music also that you all play and bring. And when is the next big gathering?

Daniel: Of course! Great music and great conversations! The gathering is going to be in 2022 in Athens. That’s going to be a great, great meeting. What a wonderful place to talk about music.

Sree: We have comments coming in now from all over. Lisa says she loves hearing your perspective. I see my dad is watching in Kerala, India! “Hi, dad!” It’s great I get to see you this way because we can’t travel the way we used to. Professor, tell us what ‘s like now that you can’t travel like you used to.

Daniel: I spend more time with the kids and my lovely wife, so it’s been a very nice time. But also during this time, I’ve found myself thinking a lot more about music and I’ve begun making videos, not just to keep me off the streets, but because I think there are important things that music has to say during this time with the pandemic.

MUSIC AND THE PANDEMIC

Sree: We’re going to show some of those clips, but first, Linda Lawrence says, “During the crisis of the past few months, I’ve been listening to a lot of Bach, Handel, and Vivaldi. Finding a lot of healing and the order manifested by this type of music helps me with my daily life.” So if I may put you on the spot, what is the difference between these three musicians, these three composers, that we can understand?

Daniel: Bach, Handel, and Vivaldi are great Baroque composers. Vivaldi actually was an amazing composer. He had so much drive and energy. He had red hair, he was an Italian. If you listen to his music — I’m sure you all know the Four Seasons — that music is incredibly creative and it has this way of just moving towards these cadences. Bach was very excited by Vivaldi’s music. He learned a lot about building these internal structures from Vivaldi. Of course Handel is a great composer, from the German-speaking lands to Britain, and a composer of great choral music in particular. And he’s the composer that was, in fact, the most famous composer at the end of the 18th century. They had forgotten about Bach and Vivaldi by then, so Handel had the greatest influence. Particularly the Hendelian style, that great kind of sublime, very grand, Baroque style that a lot of people imitate, including Beethoven.

Sree: That’s so interesting that some names that might seem bigger now were not the stars of their day, right? This demonstrates the ebbs and flows of time.

Daniel: Reception history is always interesting. Bach became really famous after Beethoven in a funny way; Mendelssohn revived the cinematic passion, and so then there was a Bach revival. Even before that, Bach’s son Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach was in fact the more famous Bach and in many ways, very influential.

Sree: So there was more than one Bach and the junior Bach was the more famous, but then the daddy Bach became more famous over the centuries?

Daniel: Very complicated story. But basically, yes. By the time he died, his music was what we regarded as a little bit too cerebral. A little bit too turgid, some people used to say. But his son Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach was very well known, particularly as a keyboard player, and for music that was emotive and whimsical, wonderful music. So he was far more famous than his dad. And then it took until the late 1820s and1830s for Johannes Sebastian Bach to come back. There was a kind of revival because Mendelssohn had converted to Protestantism and very much wanted to be in that sort of looser line. He was very interested in Bach music and put on this fantastic performance in Leipzig of Saint Matthew’s Passion that drew massive crowds of very important people, and that really started a revival of “daddy Bach” as it were.

Sree: For those just joining, we’re talking with Professor Daniel Chua of Hong Kong University as part of our series on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. We’ve got a question from Minnie: “Which composer’s works do you think are the most healing? Someone once said, ‘Bach’s music could be sold in the pharmacy’.”

Daniel: I find Mozart, particularly the piano concertos, very…I don’t know whether the word is “healing” or “soothing,” but there’s something about this music that puts this huge, delightful smile in my heart actually. I think the theologian Karl Barth always talks about Mozart as a composer that is able to express the dark side of life but in a way that brings great joy. There’s a kind of playfulness in Mozart that I think brings a great deal of healing. Bach, of course, partly because this is always, in some sense, sacred music, even his secular music is really sacred. It always brings that sense of the divine in that there is an order to this world, a structure that we live in where we can find meaning, and you can always hear that in Bach. I work on Beethoven and particularly late Beethoven, so to me, I think the music of late Beethoven really deals with many of the most critical issues head-on, and he’s always able to find a way of transcending suffering and pain without minimizing the suffering that he’s going through and some of the issues that he’s struggling with.

CLASSICAL MUSIC PANTHEON

Sree: I used to be the chief digital officer of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There were a few, kind of like, rock stars, names like Picasso, Monet, Rembrandt, and Da Vinci. All those names are ones people know. There’s kind of a competition about who’s the most popular. What is it like in the world of classical music? What is the pantheon of the greatest names that people should know? Who should be elevated to that pantheon?

Daniel: The idea of classical music is all about that pantheon, who gets to get their name on that concert hall, or on the ceiling of the concert hall. Beethoven is always, because he was so big in the 19th century, is always in the conversation; a concert hall always has a big bust of Beethoven. Of course, everybody was trying to be in his lineage. So people invented Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven as the so-called classical composers. And then of course, everybody was fighting to say, “Well, I want to be that too.” So we know Brahms would fight and Wagner would fight that. So actually, we’re not dealing with a history of music when we talk about this pantheon. We’re just dealing with this lineage of greats.

Of course, there are many other composers that we never talk about very much, for whatever reason. Why are there only three classical composers, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, in the late 18th, early 19th Century? What happened to all the other composers? There can’t just be three composers, right? So we have to be a little bit careful when we try to have our great pantheon, because it also means that we miss out on a lot of other music that was there. We always say, it’s all about Beethoven symphonies and all that, but actually, people were really interested in choral works, operas, and other chamber music. So there’s a very rich history and we should be careful not just to have the pantheon. We need to have a much broader view of all the music that is being made and have a greater understanding of that context.

Sree: We’re now going to watch a couple of videos the professor himself made during the pandemic. Professor, why did you decide to make them and what is the reasoning behind them?

MUSIC THAT SPEAKS

Daniel: With your phone, you can do quite interesting things. I wanted to record myself, in quite a kind of new format for me, in some kind of sharing about what I thought would be helpful at this time of COVID-19. They’re not really lectures, but I thought this might be a good format for speaking to a broader audience. So I made a couple of videos, one on Schubert, and one on Beethoven, and I just set myself the question, what kind of music would be appropriate now, during this time of COVID-19? What music would speak to us, not so much entertain us, but speak to us about some of the issues that we’re facing at this time?

Sree: All right, so tell us about this video that’s coming up. Tell us what we will be seeing.

Daniel: This is on Opus 110. A sonata by Beethoven. This is a sonata where Beethoven sort of composes a kind of breathing-difficulty sound, like the music is having asthmatic spasms. So to me, this is the music they really speaks to when people need ventilators. He goes through this music, and when it comes to the end of this piece of music, he’s able to really breathe in this very large phrase. It seems to me that the music is all about breathing difficulties, and then breathing out spaces of hospitality. He begins this sonata with a very strange expression mark called “con amabilita,” meaning “with amiability” in French, or “with hospitality.” So this is a sonata that is trying to welcome people in.

Sree: All right, here we go.

Daniel (on video): The entire sonata is about the amplification of friendship, even through the darkest moments, and, structurally speaking, Beethoven does just that. He takes the first four bars, the Motto theme, and he amplifies it. First it becomes a longer phrase. And then it becomes more and more capacious as it builds into larger sections. Beethoven is taking in more and more. He’s creating a breathing space, he’s giving time to welcome the stranger and to create that space for friendship.

Sree: Very, very nice. Tell me about that music; which rendition is that?

Daniel: Oh, that was me! With all these copyrights and permission issues, I have to find music that I can play myself so that I don’t get into any trouble. So that’s me playing in the background while I was talking.

Sree: All that by yourself. I loved it. You even had special effects going on? I think we all want to listen to more. Behind you, we’re looking at your desk now. Tell us what’s on your desk right there.

Daniel: This is the autograph, a facsimile autograph, of Beethoven’s Opus 110. Piano sonata.

Sree: Oh, wow, what a magical document. And what do you have on the stand behind you?

Daniel: You always have to have Bach somewhere, right? Otherwise, you won’t have any structure in your life. You got to have some Bach, some Beethoven, and it keeps you sort of grounded and happy.

MUSIC BORN OF CRISES

Sree: We’ve got lots of people watching from around the world, folks. There are experts watching as well, trying to think about the role of music in giving us hope and healing during this very difficult time. I want to ask you, professor, in the times when some of these classical heroes were doing their work, were they in times of crisis too?

Daniel: Absolutely. I mean, I think one thing we forget about this pandemic is that infectious disease was something that was very, very normal in the 19th century, in the 18th century, all the way back. So people like Beethoven or Schubert, they literally suffered from infectious diseases, or were in fear of infectious diseases, all the time. So this theme runs through music in many different ways. I did one video on Schubert, who himself died of an infectious disease and he knew he was going to die. When you listen to his music, you can almost hear that kind of foreboding, and an attempt to come to terms with the consequences of infectious disease. And in that particular Beethoven piece, he suffered greatly not only with deafness, but himself was often very ill. And this piece has moments where he is almost in a state of losing life, losing breath. The music actually says, he’s exhausted, and he’s running out of breath and it’s a kind of lament.

But what I want to point out about this music is that even though the music is about lamenting and suffering and isolation, we want to listen to it. In other words, this music is extremely beautiful and that is a crazy kind of tension. Even though it’s about something that is very depressing and sad, the music points to something that is very beautiful. In other words, there’s something that is transcendent. So even when there is suffering, even when you are in those dark, dark moments, the beauty in the music always is transcendent. It always points to something beyond. That’s why I think in the music, there is always a sense of hope.

Sree: Mark says there’s great music from Durham, North Carolina. Talk about American music and its influence on the world, please.

BEYOND CLASSICAL

Daniel: Not my area, but America has its own group of composers, particularly in the 20th century. Aaron Copeland would be a kind of representative, but it’s a kind of a very fraught issue actually, in America. What constitutes American music? Who gets to have that voice? What kind of scenery expresses what it means to be American? What does it mean if I appropriate this music and that music from other native groups? What does it mean when I do that? Even if you go back to the 19th century, you have to remember Dvořák visiting America, writing his New World Symphony and taking music from the Native Americans and putting it there. So, you know, we’re already beginning to ask questions. What does it mean to write American music, because jazz is the other interesting idiom that really influenced the entire world, and that begins to seep into classical music, not just in America, but across the world. Even as early as the 20th century in Paris, people were really working on incorporating elements of jazz, maybe not really understanding it in its fullest form, but in a way, blues and jazz is the quintessentially American music and probably the most influential if you follow its history.

Sree: William Lai, a former student of the professor, asks, “Could Wagner music be called healing?”

Daniel: Wagner also is a tricky composer because of his links with fascism and his hatred and anti-semitism. He’s a very complex personality. What I always say about Wagner, he wrote 10 volumes about himself. This is not just the music, this is just writing. So you should always write as little as possible about Wagner. I think music can be healing and it doesn’t really matter who the composer is, because sometimes we think that music is about the content of what it expresses, but the music is more than just that content. The music is about creating structures, rhythmic structures, and these rhythmic structures are a way of weaving experiences of time. The wonderful thing about human beings and a very unusual trait that we have is that we have this thing called entrainment, which basically means that we tap our feet to rhythm. No other species really does this, you might find an occasional parrot that might be able to nod his head to rock music, but you won’t find two parrots that will do that at the same time. And because we have this thing called entrainment, we’re actually able to share our experiences of music with one another. Now we can listen to that Beethoven sonata together and we can share that experience of time together, or we can be improvising jazz, and you can be improvising with me: we’re sharing that experience of time together. So in a way, music is always healing in some sense, because music is never socially isolated, it is always a relational thing. And every time you’re in relation with someone, you’re in dialogue with someone, you’re connecting with them; the elements of healing are being negotiated if you’re making good music together.

Sree: We have a question from Eeshaanee Shandilya. who asks if you can throw some light on the music of Johann Hummel and the influence of composers like Mozart and Beethoven on his music.

Daniel: Hummel. Yes, he’s one of these composers who kind of gets missed out on. We talk about Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, but Hummel was also a great pianist. He gets sidelined in many ways, even though people like Schumann and so on were playing Hummel. I don’t really have a lot of light on his music, except that I think we should really listen to all his music. He was certainly influenced by Haydn and Mozart and Beethoven. If you look at people like him and other pianists, they were very important in developing a 19th Century piano playing style that changed the way we understand piano music and the birth of the piano recital. Even in Beethoven’s time, nobody would go to a recital of just piano music, but then we began to have these virtuoso pianists with a very different kind of technique that would then result in people like Schumann and Brahms writing great piano music that involved much more virtuosic work, involved a lot more moving around of the arms and hands. That didn’t really happen much earlier on in the 19th Century.

Sree: Linda says, “Name a favorite Beethoven sonata.”

Daniel: Apart from Opus 110, there’s Opus 109. This is music that begins to go off into a kind of, I don’t know how to describe it, a world of texture, and a sort of filigree where it seems as if Beethoven is just playing around with conventional figures but somehow imbues all this very conventional stuff like trills and arpeggios with a great deal of meaning. I don’t know how he does it, but he does it. It is the most profound music you can imagine. The variation movement at the end sort of strips the theme away into the most extraordinary sort of dazzling fireworks of these filigree things and then you think, “Wow, can it get any better than this?” And then the theme comes back with him, and you get the most incredible sense of stillness and if you’re talking about peace and healing in that moment, you really feel as if you’ve arrived home. You really feel it as if you’ve arrived at a moment where you can be at rest. It’s a great piece of music. I recommend it to everyone.

Sree: We have another video we’re going to play now. So tell us what this is.

COMPOSING TIME

Daniel: This is also from the same video on Opus 110 by Beethoven. I think it’s really about how when you compose music, you are actually composing time, and you can compose time as it rushes by. It’s very self-determined, time, it doesn’t really care about you, it just zooms past. Or you can compose it. Music creates a huge sense of time, of invitation. My point here is that this music is really about friendship and love because love is a four letter word spelled t,i,m,e. Time is always something that we can give as human beings. And what Beethoven is doing here is giving time. He’s saying look, I want to create as much breathing space, as much time, as possible, because I want to welcome you into this sonata. And that’s really what this bit of the video is about.

Daniel: (on video) So Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Opus 110 is about the redemption of breathing. If you don’t believe me, Beethoven says it himself. In the very last section of the sonata. He says that the music is reviving, little by little, the music is bringing in new life. So ultimately, despite the suffocating lament, this music is about hope. It is about life after despair, the music keeps on giving and it never gives up.

Sree: That was really, really nice. The fact that you put that together yourself is really cool. We have several questions coming in. Lisa asks about how to make classical music more approachable. Mark asks about how to make sure that people who should be known become known.

Daniel: Classical music can be more approachable if we talk about it a little bit more and not expect people just to sit quietly in an audience. It can be very, very intimidating, just to turn up in a concert hall. We expect that you should just sit there in silence and you should know what you should be doing. But actually, people don’t, and sometimes they don’t know how to listen to this music because nobody’s going to try to help them. One thing I try to get people to do, particularly musicians that we invite to Hong Kong, is for them to talk about how they perform this piece of music. We have a great “Music in Words” series, where the musicians actually talk about these pieces before they play, and that really helps people get into classical music. If you really want to open up the field and to lesser known composers, we have to start programming these composers in context with the more famous names so we get a good balance of the other canonic works that we know so well.

Sree: Can you talk further about the image from the video that we saw behind you on your desk?

Daniel: This is from the facsimile score of Beethoven Opus 110, and it’s an extraordinary moment where the music is about to die. It feels like Beethoven is giving himself the last rites. Instead of landing on this minor depressing chord, he suddenly lands on this G major chord. But the funny thing about it, if you look at the image, is that the chord is on the upbeat. So it keeps repeating itself on the upbeat. It repeats itself many, many times as the pedal is down so it gets louder and louder. It’s as if Beethoven is doing this: he’s breathing in and he’s breathing in, he’s breathing in and then he breathes out. And then he breathes out, he has this enormous, enormous phrase. It leads all the way to the end of the movement at the end of the sonata. And it’s one of the most amazing, triumphant, joyful, life-affirming moments you can imagine in music — music that is very affirmative, very healing in the sense that it gives you a sense of what life should be like after all that sort of lament and suffocation in the middle of this particular sonata.

Sree: We’ve been asked to speak again about the particular pieces of music you were talking about. People are joining us all the time from around the world, and are asking to hear about them again.

Daniel: I was speaking about Beethoven’s Sonata Opus 110. I also talked about the previous sonata, Opus 109 in E major, particularly the last movement, but the whole sonata is amazing. And then we talked about things that I particularly enjoy, such as Mozart piano concertos. If you’re looking for one, one of my favorites is the A major Concerto K. 488. I think that one is the perfect Mozart piano concerto.

Sree: We would love to have that. We’ll talk to our friends at HKU to create the Daniel Chua playlist for Spotify. We also have here an image of Beethoven. Tell us what you see when you look at this painting.

MISSA SOLEMNIS

Daniel: This is a very famous portrait of Beethoven that was done in his lifetime. He’s actually holding, if you see the whole painting, a score of his great mass, the Missa Solemnis. This is a very Beethoven kind of look, and these are supposed to be the eyes that look up to the heavens. But you can see that in that kind of very furrowed brow and we often think of Beethoven as a person with this kind of classic stare, this kind of heavy furrow. It’s a very, very serious look. But I always think that actually this is the wrong image of Beethoven. He’s really not a person that always has that very serious, heroic kind of look, but he’s actually a composer of great tenderness. And one of the best composers that knows how to get across the idea of love and friendship. So I’m always championing a different view of Beethoven, not always that very macho, heroic Beethoven, but a Beethoven that is much more broken, much more fragile, much more vulnerable; A Beethoven that really speaks far more in this time of COVID-19 than that heroic figure that ashes through everything. I think that it’s not the right approach in this time of pandemic and protest. He’s a figure that has really learned how to be humble, how to listen, and how to love.

Sree: I’m sure you want to say hello to Helen Woo. She’s a past HKU music librarian from Toronto. She says, “I play the piano, sing ,and listen to classical vocal music more during the pandemic to cheer myself up.”

Daniel: that’s a very good thing to do. I’ve been doing the same.

Sree: Do you have an iPod or an iPhone that you listen to music on, or do you only listen with the best, big stereo system?

Daniel: I love big stereo systems. The music I tend to listen to lately is the Waltz, from Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings. I think that’s one of the most perfect pieces he’s ever written; it always brings a smile on my face. Elgar’s Allegro for Strings is also an amazing piece that I just love so much. I listen to a lot of Mozart and a lot of Beethoven. Yeah, I should really get a song list.

Sree: Do you have space in your library for modern music, current music, hip hop, other kinds of music?

Daniel: Absolutely. We cover all of that actually. As I said, musicology is not just about classical music, but about all music. We need to understand that we need to really delve into all these different aspects in order to get a really a broad view of what music is, what it does, the cultural work that it does, why it means so much to us, and why it’s something that really brings a sense of both joy and healing, and really helps us to think about some of the deeper questions at a time like this.

Sree: Professor, before we let you go, we want to show your book jackets so that people can also read you and learn more about you. So talk about each of these three books, please.

Daniel: in the Galitzin Quartets of Beethoven, I think you need to be interested in the notes. This is a very music-analytical book about the late quartets of Beethoven. If you don’t know the late quartets of Beethoven, you must get to know them. The most amazing music. Absolute Music and the Construction of Meaning is a fun book written in 35 very short chapters, full of puns, very light-hearted, but asking some very deep questions about why Western music is what it is, why we listen to Western music in this way and what it means.

And the book Beethoven and Freedom is trying to talk about, in what sense does Beethoven’s music reflect the notion of freedom? We always associate Beethoven with revolutionary freedom, but there’s much more to Beethoven than just revolutionary heroics and I wanted to get that across in that book. Also if you want to check out the International Musicological Society website, you’ll find my videos in the section that we call “Music logical Brainfood;” we’ve also welcomed other musicologists to send their videos on music in this time of COVID-19. You can also check out the HKU Muse website, which is where we have our concerts. There are many videos there with me and other colleagues talking to great musicians about their performances. So if you want to find out more about classical music, those are the places to go.

Sree: In this series of global conversations, we also had a COVID Cadenza that we did with HKU students. It was amazing to see and hear that. Talk about your students if you can, give a shout out to them.

Daniel: We have the most amazing students because music students are always amazing in general. But you know, they’ve had a hard time because it’s not easy to teach music online, particularly when you need a lot of interaction. So they’ve been working really hard and trying to get around all these difficult problems. But we have some great performers, you heard them in the COVID Cadenza online broadcast. They are virtuosos. We like to mix. We don’t really make a distinction between Western music and Chinese music and so on. It’s all music. In our curriculum, it’s just “all music.” We study them together, we try to break the barriers between things.

Sree: This was on April 23, so people can go back in the archives and find them all there. It was so well done and your students were very, very impressive. So we want to say thank you very much to our Professor Daniel Chua. I hope everyone will think about the power of healing and music at this moment.

Revisit the live show: