A global conversation with Prof. Keiji Fukuda: Policy Lessons from Asia

Revisit the full interview here

(Note: In this transcript of their dialogue, Professor Sree Sree. nivsan is informally identified as Sree and Professor Keiji Fukuda is KF; the transcript has been edited for readability and length.)

Hello, everyone. My name is Sree Sreenivasan. I am the Marshall R. Loeb Visiting Professor of Digital Innovation and Audience Engagement at the Stony Brook University School of Journalism. Welcome to this live global conversation on the COVID-19 pandemic sponsored by the University of Hong Kong. This is part of a series to learn lessons relative to the pandemic in Hong Kong and Asia. We’ve spoken to experts in medicine, public health, and economics.

Today, our guest is Professor Keiji Fukuda, Director of the School of Public Health at the University of Hong Kong and also a member of the expert panel advising the Hong Kong government on COVID-19 issues. Professor Fukuda is a former Assistant Director General of the World Health Organization, the special adviser to the Director General on pandemic influenza and Director of WHO’s global influenza program. At WHO, Professor Fukuda also led field investigations related to global outbreaks such as SARS, MERS, and Ebola. Before joining WHO, he worked at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and led field teams that assisted Hong Kong during the emergence of Avian influenza in 1997. He has worked closely with China on issues such as influenza, its surveillance and SARS.. He received his BA from Oberlin College and his MD from the University of Vermont. He also earned a Master’s degree in Public Health from the University of California at Berkeley.

TWO MILLION AND COUNTING

Sree: Before we begin, we want folks to get to know you a little bit, professor. Like me, you were born in Japan, and then you moved to America and ended up studying at Oberlin, a great liberal arts school. Talk us through your career.

KJ: My family moved to the states when I was a baby and I grew up there. But for whatever reason, I also wanted to travel and see much of the world and although I grew up in a very Asian family, my parents let me do it. So through my educational period, I saw a number of places, including Hong Kong, back in the 1970s. My career has allowed me to keep traveling and that’s been one of the big joys in my life. I’ve gotten to work with fantastic people in many countries and continue to be able to do that by coming here to Hong Kong. It is one of the cities that I’ve enjoyed the most in my life.

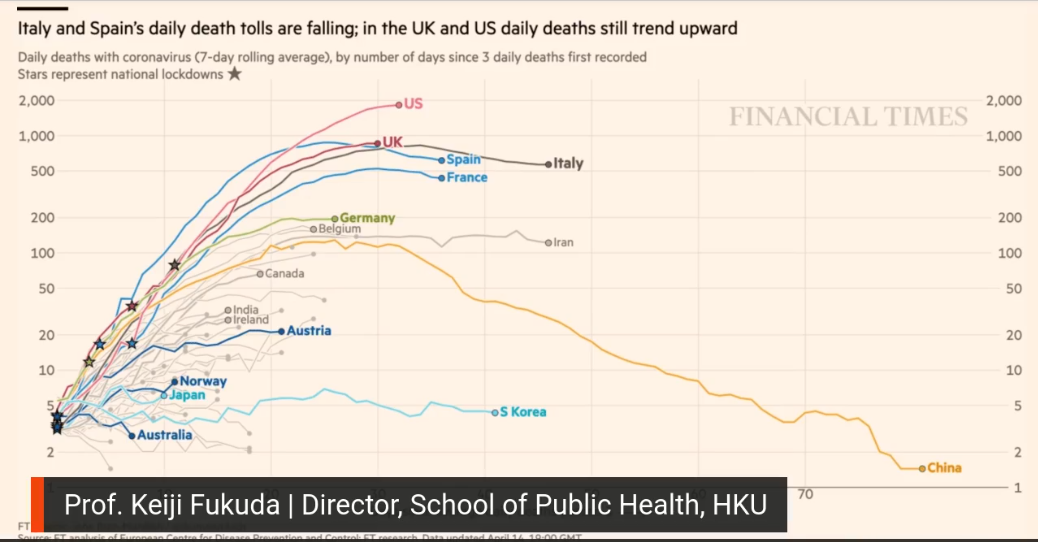

Sree: Today, in terms of COVID-19 cases worldwide, we crossed the two million mark. As you look at this chart in this Financial Times showing where the cases are, what are you thinking when you see these numbers?

KF: We’ve all been looking at these numbers for the last few months and how the dots showing the regions with the most cases have shifted. A few months ago, we would have seen the heaviest numbers in Asia, but now, you can see Europe and North America as the regions where the heaviest activities are.

Sree: We often talk about flattening the curve. Let’s look at some of the curves shown on the Financial Times map, which we recommend everybody check out daily. What are we learning from looking at this?

KF: There are a couple important things to pick out. One is that if we look at the curve for China, it should hearten us that we can bend the curve. It can be done. Second, when we look at the curves that are highest up, such as those for the US and Italy, it shows that in different parts of the world, bending the curve is still not assured. I hope this pushes everybody to keep up their efforts. After so many weeks of very difficult work, that’s hard, but we have to keep doing it.

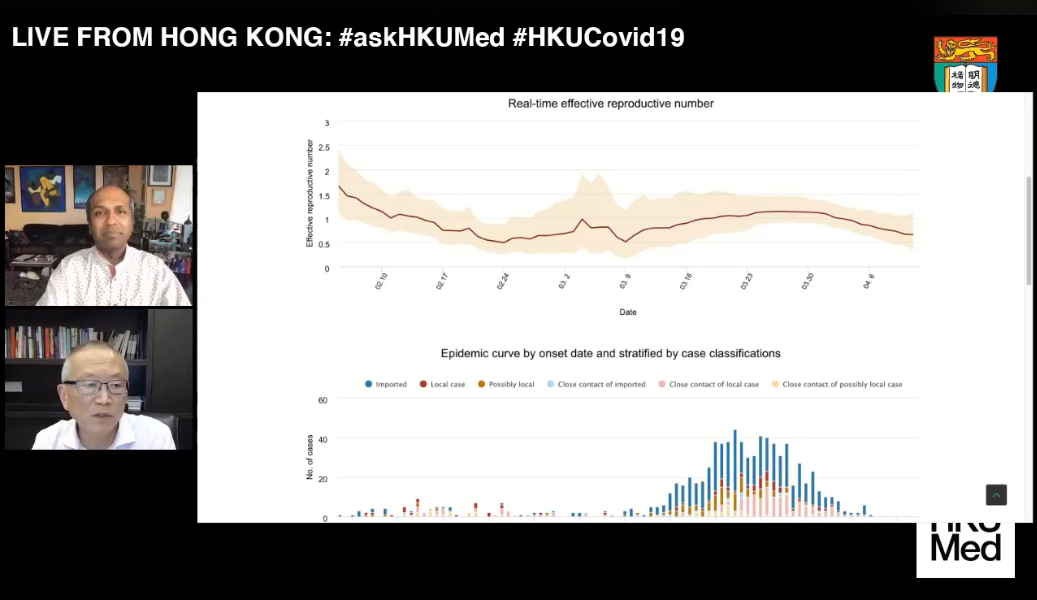

Sree: We also have a chart that shows us the curve in Hong Kong. What is it telling us about Hong Kong?

KF: The Hong Kong curve is instructive for understanding what’s going on. The curve represents cases which have been occurring in Hong Kong over time. For the first period, from January up to the middle part of March, the number was relatively low. Then in mid-March you see a big surge in cases. At the time, everyone wondered whether the situation was getting out of control. But when you look at the colors symbolizing the different cases, with the blue colors representing travelers, what the curve really reflects is that as the pandemic became more active in all parts of the world, Hong Kong cases grew because people wanted to come home. The blue colors show cases of infection in people returning to Hong Kong. As things got more dicey overseas, people got worried, they wanted to go home. This is going to be a challenge for everyone everywhere.

Later on, you can see the curve start to come down. It’s coming down in part because the government in Hong Kong studied what was happening, and then took action based on what was being learned.

UNWELCOME NEWS

Sree: How do you think the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has performed through this crisis?

KJ: The CDC has had a tough time. It is one of the premier public health institutions in the world, with a depth of expertise and experience very few organizations can match. But it did have some difficult times in the beginning with coronavirus testing. And it has not had as much of a prominent role in the public as it normally would. Nonetheless, I know my colleagues back there and they continue to do the work that needs to get done. They are applying their epidemiologic and laboratory expertise. They’re working very hard on this.

Sree: We have questions coming in from around the world for this videocast. We have Mara watching from Toronto, and we have friends watching from Bangkok. And I saw Cynthia from Brooklyn. Linda’s watching from Long Island. Professor, this interconnectedness, that’s part of why we’re in this situation, right? People get on planes for their work in other countries, and goods and services are exchanged all over. That’s why, in part, we’re in this situation.

KF: Exactly. In our lifetimes, one of the major factors, if not the major one, shaping outbreaks has been globalization. It’s made it easier for these infections to travel around the world more quickly. But it’s also given us the capacity to be able to respond more quickly than ever. And so COVID-19 in that way is like every other outbreak that I’ve been involved with the past couple of decades; it exemplifies both sides of globalization’s impact. This linkage, this interconnectedness, is everything, both on the threat side and for our hopes for getting through this as well as possible.

Sree: What are your thoughts about the US cutting funding to the World Health Organization. You used to work there, as a senior official and on field teams, and so you understand WHO better than most. What is its role and the impact of this threat to cut funding by the President of the United States?

KF: The news is unwelcome for several reasons. First, it’s important to know that every major outbreak since the Spanish flu epidemic in 1918 has had one common lesson — no country is an island in the face of outbreaks. That understanding has been the basis for some of the biggest breakthroughs in addressing pandemics and the basis for countries to adopt WHO’s International Health Regulations in 2005. It also was the basis for initiating and successfully completing another framework, the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework, and for this idea called global health security, which is that countries need to work together when faced with a common threat.

All of that requires a multilateral approach. And if you’re going to have a multilateral approach for urgent situations, then you need an organization to be at the center of that group of countries working together. All countries, including big countries like the United States and China, depend on WHO to provide information and perspective. Poor countries depend on WHO for broader support, such as offering policy input, but also material support, in the form of putting experts on the ground and providing pharmaceuticals from the private sector and so on, all of which is usually coordinated by WHO.

Different countries have different roles to play in dealing with public health issues at the global level. So if we think of the smallpox and polio eradication programs, much was made possible because of US involvement and leadership, and in providing political and financial backing. And so the announcement marks a stepping-away from that. Whether President Trump actually follows through or not, it’s a bit like the announcement when the US indicated it would step away from the Paris Climate Agreement; it sends a tremor through the international community. In the long term, it’s going to weaken both the US, which depends on other countries, in terms of addressing health issues. It’s also going to weaken the world’s ability to deal with these complex issues. I hope he doesn’t follow through on it. It’s really quite bad news.

HERD IMMUNITY AND SECOND WAVES

Sree: Herd immunity. It’s one of those things we hear about and people think they know what it means, but they don’t really know what it means.

KF: Herd immunity is basically the idea that if enough people in a population get immunized or are immune against an infection, then it’s much harder for the infection to basically move around and infect people who are not immune. Basically, if the group’s level of immunity is high enough, everybody benefits. The idea is sound; the question is, how do you achieve it?

In essence, there are only two ways to achieve herd immunity. First, the population develops immunity through the infection itself. We don’t know the exact percentage that has to get infected for COVID-19, but most the models assume it’s going to be somewhere about 60 or 70%. The second way to achieve herd immunity, of course, is by vaccination. We have a number of companies working on vaccine development, although it’s unrealistic to expect to see the first of the vaccines until next year.

We all would like to achieve levels of herd immunity and we would like to achieve it through vaccination. The problem with achieving it through infection of course is that with something like COVID-19, you can expect a lot of people to get very seriously ill and you can expect those seriously ill people to overwhelm hospitals. You can also expect a lot of those people to die. So in Hong Kong, we very much do not want to achieve herd immunity in an uncontrolled way, but would like to make it through until we’re able to get to a vaccine.

Sree: What is your prediction on a second wave in Asia, Singapore, Japan, Hong Kong? We’re already seeing it sort of happening in some places.

KF: The way I typically think about this issue is, how long are we going to be at risk for infection? Sometimes people talk about having a single wave and hope we don’t have additional waves. But that’s unlikely. In Hong Kong, we initially had low levels of infection. We then, as I mentioned earlier, had a surge of several hundreds of cases over four or five weeks. That surge in cases was caused primarily by a large number of people returning to Hong Kong with infections.

However, that same shape of curve could have been caused by other reasons. It could have been caused by an outbreak occurring solely within Hong Kong. Right now, as far as we know, most people in most countries remain susceptible to infection. And so it’s quite likely that even countries like China, which have reduced their infection rates down to quite low levels, remain at high risk for seeing additional infections occur. All Asian countries, and all countries elsewhere, are going to be at risk for multiple waves of infections occurring over the next several months.

Given that picture, the key things are to make sure that surveillance and monitoring systems are working as well as possible. I think the most successful countries have relied upon a lot of testing to help assess the true situation within the country. So yes, I do think that it’s likely we are going to see additional waves of infection. And the key thing is making sure that we take steps to reduce the harmful impact of those additional waves.

Sree: You’ve travelled to India for WHO, you’ve worked as a medical student there, so tell us about India’s approach and its nationwide lockdown. Why is India, with its 1.3 billion population and where many regular health outcomes are poor, why is India doing pretty well on that chart we showed earlier? My instinct, even with the lockdown, would be to imagine India having worse outcomes than they’re having at the moment.

KF: A lot depends on your capacity to do testing and really know what your infection rates are and how many cases you have. India’s population and its forms of governance make it very challenging. India has a central government, but also very strong state governments. It also has many different languages and cultures. It’s a very complex country. It’s clear that if there are no efforts to try to reduce the spread of COVID within India, it could end up with a very large number of seriously ill people. Right now India appears to be just at the early part of the outbreak. But the cases are beginning to increase rapidly. And as you know, curves start out slowly, but they can pick up speed very quickly.

The options for India are difficult. It’s possible to continue the current lockdown for a short period of time. But how long that can be extended is a very real question. My sense is that it’s going to be difficult to treat India as a single entity in terms of trying to exit from some of the lockdown’s control measures. And that it may have to be done more or less on a state-by-state approach. In many ways, that is not optimal because, depending on the control measures, you can have people traveling from one place to another. But again, given its complexity and size, it may be India’s only realistic option.

CONTROL MEASURES AND VACCINATIONS

Sree: Harvard research in the academic journal Science says intermittent lockdown measures may have to be imposed until 2022. What do you think about that? And just generally, are you in the prognostication business? Do you try to make predictions? How do you approach questions like this, including this particular research if you are familiar with it?

KF: I am not in the prognostication business and I usually try to escape making any kind of predictions. But the general idea that it will be necessary both to respond to the current situation by establishing control measures, and then backing away from them when case-activity levels go down, is realistic. The Harvard researchers had been working with HKU colleagues, and this idea of both suppressing and lifting over time, until we are able to vaccinate a large part of the population, is realistic.

In essence, it’s what we’re practicing here in Hong Kong now. We started out with certain control measures when the activity was relatively low. And then when there was a surge in cases, the social distancing measures and the border control measures were stepped up. Hopefully, now that the cases have been in single digits the last number of days, we can begin to lift some of those social distancing measures so people can go back to a more normal level of activity. But we also recognize that if there is another surge in cases for whatever reason, then it may be important or necessary to re-establish stronger social distancing measures.

Sree: On social media, some people are saying vaccines are fake. How do you combat this kind of misinformation? Or when misinformation or disinformation sometimes comes from unexpected places?

KF: How to deal with misinformation has been one of the most difficult and still unsolved problems. We don’t really quite know how to counter all the misinformation out there. And as you know, it can come from the highest levels. It can come from unnamed sources on the internet. it can come in many different ways.

Vaccines have been the subject of a huge amount of misinformation for decades. Strong efforts have been made to discredit their importance when in fact they are one of the major breakthroughs in public health history — the ability to protect people before they get infected. The situation requires authoritative sources of information and well established individuals and organizations to be quite active in terms of communicating what is truthful and what is misinformation.

But it is a difficult job. Some of the rumors that I hear now have come up during other outbreaks. During the 2009 influenza pandemic outbreak, there was a lot of misinformation — about how vaccines were intended, for example, to harm people in different countries. I won’t go into all of them. But it is an issue that we still don’t know how to effectively deal with.

REINFECTION AND SENIOR PROTECTION

Sree: We are hearing cases of people testing positive after they were discharged from hospitals after being treated. So there is this confusion. Some seem to recover, go home, and then get sick and pass away. How is that possible?

KF: Yes, it is confusing. And it’s a question that comes up a lot — whether people were reinfected after apparently getting over their illness. I think that the likelihood that there’s real reinfection going on remains pretty low. However, it’s not zero. There are studies showing that even when you have a measurable antibody response, your levels of neutralizing antibody can be quite low. Whether that equates to having less immunity remains to be resolved. It’s also clear that some people can remain antigen-positive for longer than others. Whether that equates to them being infectious is another question.

Sree: In a post-lockdown scenario, what is the way to protect seniors?

KF: The basic idea for protecting seniors, whether post-lockdown or in lockdown, is very similar. We know the elderly are in general at the highest risk for developing serious disease and for dying from COVID. Without having a vaccine, we want to keep them as shielded from infection as much as possible. That means following all the recommended public health or personal health measures which have been recommended: Avoid going out or mixing with large numbers of people. If you do go out, wear a mask. Make sure that you wash your hands frequently. For friends and family members of the elderly, if you are sick, and it’s possible that you have COVID or another infection, then stay away from the elderly. Again, these are things one would recommend whether we are in lockdown or post-lockdown.

LESSONS AND QUESTIONS

Sree: If we look at the curves on the chart again, we have a question about South Korea. The chart shows China doing well now. But that South Korea never went as high. And it stayed at that lower line. What does that line tell us about the work that they have done to make sure that curve stays as it is?

KF: As you remember, South Korea started off with a big explosion of cases and many of those cases were related to a cluster. But South Korea was able apply many of the things they learned from previous outbreaks. I’m thinking of the MERS outbreak in Seoul in 2015, which also took the country by surprise. What they did after that was to improve the public health system. They made the Korean CDC stronger and took other steps to improve the public health system. They learned how to do contact tracing faster and how to do case investigations better. And then they took their technological expertise and used i testing at a very high degree. These are some of the elements that were used to flatten the curve.

Other key elements were good leadership and good public communications. These are common to many of the countries in Asia. It’s very useful for other countries to look at South Korea in terms of determining what might be employed in their own countries. At the same time, it’s important for countries to put together their own recipe for dealing with COVID.

Sree: What studies have been made to determine how the virus behaves at high temperature or in tropical countries?

KF: There have been studies under controlled conditions, some by investigators here at Hong Kong University. There also have been some other attempts to look at the survival and behavior of this virus under more natural conditions. When the temperature goes up, depending on the surface, the survival of the virus goes down, but under cool and drier conditions, the virus can be quite robust in terms of surviving, and by robust, we mean surviving for days.

Laboratory studies use approaches such as placing viruses in transport media, for example, whereas in the real world, viruses are not going to be in transport media. There’s been speculation as to whether virus activity is going to be lower again in warmer months. But we have seen that the virus can be quite active in places like Australia, and in warmer climates like Singapore. So we don’t have any evidence that this virus cannot be highly infectious in warmer climates. It may be however that it develops an overall seasonal pattern.

Right now, we’re in a situation where the majority of people in the world are susceptible to infection. That probably is a strong enough factor for now to ensure that we’ll continue to see infection activity regardless of season. It may be in the future, like with many other respiratory viruses, it settles into more of a seasonal picture. We’ll need a couple of years to see whether that’s true or not.

REOPENING AND TRAVEL

Sree: Regarding the debate in the US about reopening the country to save the economy, what kind of preparations are needed before reopening. What are the experiences from major Asian countries?

KF: Like the US, India is a large country with many different cultures. As mentioned earlier, it has a political system which is federated to a certain extent, and centralized to a certain extent. Given that situation, there are things that are needed before we try to normalize activity. One is that leadership at all levels has uniform clear messaging. A second is a surveillance system able to monitor accurately. The US has greatly increased its testing capacity, but it can increase it and other capacities even more. Fundamentally, the question for all countries is, what is the balance between disease control and normal economic and societal activity? Choosing that balance is not a science question. It’s what is acceptable in that country, and that’s going to vary from country to country.

Once a country has an idea of what balance it’s willing to accept, then the question becomes what are the means that it’s willing to use to achieve that balance. Is it willing to use extensive testing? It is willing to use extensive monitoring to get back to a more normalized level of activity? The US has all the technical capacity in the world it needs. What it’s missing right now is leaders on the same page in terms of consistent messaging.

Sree: Can travel return to normal before the world’s population is immunized with vaccine? What percentage of the world needs to be immunized? What percentage needs to be vaccinated before it can be considered to have taken effect.

KF: With COVID, there’s the crisis aspect , which is the emotional and urgent part. Then there’s the actual disease control, and these are not necessarily the same. That’s one thing to understand. As soon as we start getting a vaccine coming out, even if the amount is not enough to vaccinate everyone, it will do a lot towards relieving much of the tension in the world and restoring confidence. In terms of how much of the population we want to vaccinate, presumably we’re going to want a world that is relatively immune. This is going to mean vaccinating billions of people. Right now there are more than seven billion people.

In terms of travel returning to normal before we have a vaccine, this issue will push everybody to make their own decision. If there is no vaccine, how much is it worth to travel somewhere versus the risk of getting infected; that’s going to be an individual choice. The same choice will exist for businesses. Businesses have greatly expanded their communicating via electronic means. Will they prefer to continue doing that? Or would they prefer to have face to face meetings?

MASK-WEARING CULTURES

Sree: There is strong resistance against preventive measures such as mask-wearing from UK scientists and medical advisors. They argue that if you wear a mask, you can’t drink tea, or that the mask makes people either too insecure or too secure. There seems a fundamental division on this between Asia and the UK and America. In Asia, mask-wearing is a sign of politeness and respect — you don’t want other people to get sick. In the UK and America, if you wear a mask, people think there’s a problem with you. Can you talk about that, since you’ve lived in both cultures?

KF: I can’t think of anything more in global public health that I’ve been involved with that has divided people so much as wearing masks, and this is before COVID. There is something deeply cultural about it. I would say the scientific evidence now is weighted in favor of wearing masks. A while ago, I would have said the evidence was not weighted so much that you could simply say that wearing masks is going to be the answer for preventing infections. Regardless, mask wearing is one of many steps that you need to be taking to reduce infections

In Asia, and in Hong Kong, we commonly wear masks for reasons you cited. One, we believe it reduces infections and the likelihood of infection. It’s a signal to other people that you are concerned about their health, and there’s something culturally supportive about that. These are important aspects of how we behave when we’re in a crisis situation.

It also is very clear that with COVID there are a significant number of people who can be infected, but who don’t have symptoms, but who could be exposing other people to the virus. Here, the evidence is quite strong that wearing masks can be helpful. The different cultures of wearing masks are apt to change slowly. Culture is never anything that changes overnight. But the example set by Asian countries is probably being noted by many other populations. There are many people in the West who are beginning to wear masks on a regular basis. This is one of the places where we may see a significant change on the basis of the COVID experience.

IMPACTS ON EDUCATION

Sree: How are you preparing the next batch of medical and public health students in light of COVID-19 at the University of Hong Kong, How is education impacted going forward, not just at HKU? Will students in China or India or Australia decide to get on a plane and go to America for studies this fall, when the new school year starts?

KF: COVID has had a major disrupting effect on education in Hong Kong. Many schools, including the universities, have shut down and there have been no face to face classes for months. We have accelerated the process of moving classes, small group discussions, and tutoring online. We’ve tried to continue courses on schedule as much as possible.

Because travel has been so disrupted, it has been difficult for students who are overseas to return. But on the plus side, COVID has opened up research opportunities. And we’ve tried to make those opportunities as available as possible for students interested in researching some aspect of COVID. But, bottom line, we all hope for the day when we can go back to having face to face classes. I think that it’s nice to do a lot of the teaching online, but it’s also very nice to see people in a class and just be able to talk with them.

POST-PANDEMIC

Sree: What trends in public health research and prevention do you see post-pandemic? Is this going to spark more interest in public health fields in medicine? Or will there be less interest because people are seeing healthcare workers in some countries comprise 10, 15, or 20 percent of the cases, or like in the Netherlands, 25% of the cases?

KF: COVID is going to change things in ways that we can’t imagine right now. COVID is not only going to stimulate discussion about how we protect ourselves better against future pandemics, which are going to occur, but also raise a number of other questions. Are we going to continue to have a multilateral approach to addressing crises? What does this mean in terms of governance? We’ve seen countries with different forms of government respond to the outbreak differently. We’ve seen different measures, such as electronic monitoring of individuals. So profound changes are going on.

In terms of research going beyond understanding the impact of disease, characteristics of the virus, epidemiology and so on, we have to look at the relationship between governance and culture and how we respond to these crisis situations. I expect this will lead to an explosion in research beyond any we’ve seen after other outbreaks in our lifetime. I hope it brings us also to rethink through health systems. In countries which have generally done the best, and I consider many of the countries in Asia to have done well, so far, we have seen that a common denominator has been that they have had a more unified health systems. Countries which have struggled the most have fragmented systems.

I hope we have a generation of people who work towards improving those health systems, taking what we’ve learned from this current outbreak and applying it. I desperately hope the outbreak does not scare people from going into health. I hope it shows the importance of health to virtually all aspects of societal well-being. I can’t see where all of this is going to go. But I do believe that this is the beginning of a quite profound evaluation of virtually everything.

Sree: Professor, as we say goodbye, please reflect on where we go from this? What are the immediate and then long-term things we should be thinking about?

KF: In the immediate, hopefully we have seen that when we’re in a crisis situation, you depend on other people and on your family and on your friends. You depend on your colleagues. In many ways, COVID has conspired to separate us. We had to employ social distancing successfully. But at the same time, it has deeply underscored how much we are connected and how we care about other people. That is an incredibly valuable thing COVID has given to us because we do live in a very busy 24-7 world, particularly in a place like Hong Kong.

Some of the issues I mentioned earlier are very germane. COVID has exposed that we are vulnerable in many different ways and raised questions about how we have done things in the past. These ways are not necessarily the best way for doing business in the future. We are going to fundamentally have to rethink through how we live in society. This will take a while to sort through. But I do hope that in this globalized world, we get contributions from everybody about these issues. That’s important because the world tomorrow is not going to be the same as today.

Revisit live broadcast: