Ian Holliday on Capturing the Rich Experience of Online learning

On May 7, 2020, fightcovid19.hku.hk conducted a live conversation with Professor Ian Holliday, Vice-President and Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Teaching and Learning) at The University of Hong Kong on “How we teach, learn and stay safe” in regard to Covid-19 pandemic.

Visit here for more about our live series.

Note: In this transcript of their dialogue, Professor Sri Sreenivasan is informally identified as Sree and Professor Ian Holliday is Ian; the transcript has been edited for readability and length.

Sree: Hello everyone. My name is Sri Sreenivasan. I’m the Marshall Loeb Visiting Professor of Digital Innovation and Audience Engagement at Stony Brook University School of Journalism.

Professor Ian Holliday, who has served as the vice president of teaching and learning at HKU since 2015, is with us today. He oversees postgraduate and undergraduate curricula and aspects of strategic direction. Previously, he served for five years as Dean of Social Sciences and directed a program in which students taught English to children and young adults in Southeast Asian countries. He graduated from Cambridge with a B.A and a M.A in Social and Political Studies and an MPhil and BPhil from Oxford. His research focuses on Myanmar politics and governance, which has led to several books. For his full bio, see here

Sree: We’ve been under lockdown here in New York for 56 straight days. But in Hong Kong, you’re already looking ahead and past the COVID-19 crisis.

Ian: Yesterday was our 17th day with zero local transmissions; the target is 28. We never had a lockdown, but some restrictions were placed on the use of restaurants and bars; other venues were closed. The government is now relaxing some of those restrictions, and we’re hoping we’ll soon be out of it.

Sree: We’re jealous hearing that from here in New York, the epicenter of the pandemic in many ways. We have a long way to go. What are some of the ways Hong Kong’s experience was different?

Ian: Fundamentally, Hong Kong people have been exemplary in their response. There’s been no pushback on public health requirements. Nobody has thought it’s an act of resistance or rebellion to not wear a face mask or not wash hands or not socially distance. And so in that sense Hong Kong people are the heroes of our COVID-19 story. Of course, we did go through SARS 17 years ago, and so that conditioned us to take these threats seriously. So when we learned of the first case on January 23 in Hong Kong, having already heard that the virus was spreading in Wuhan, people were already wearing face masks and being much more careful on public transport and in crowded places.

Sree: You were talking about how Hong Kong people handled it, but there it is, professor, we cannot help but compare and contrast it to the US, where people were given different directions, competing information, and a lot of false information from many different sources.

Ian: Absolutely. There are also issues here involving government trust. We went through political protests at the end of last year, which were polarizing in the way that US politics is also polarized. But in this crisis since January, people have put that aside and come together to fight COVID-19. It’s the mantra we live by in Hong Kong. You can’t take a subway train, you can’t move around the city, without seeing that coming-together around the idea that the whole society needs to mobilize to fight this virus.

ONLINE TEACHING AND LEARNING

Sree: HKU moved all classes online at the end of January, weeks and months ahead of universities in other parts of the world. Can you talk about how you decided to do it? In America, it seemed haphazard. Many top institutions gave students two days to suddenly go online. The students weren’t ready and the teachers weren’t ready.

Ian: Again, we had a trial run. I just mentioned the protests in the fall of 2019. They meant we actually went online in the middle of November because it was almost impossible to get public transport to HKU. Many international students also did not want to be here because the streets were becoming quite contested. And so we shifted online for the final two weeks of teaching and for exams in December. We expected then that we would be moving back to face to face teaching and we did that for one week in January. But then at Chinese New Year, at the end of January, the virus flared up in Hong Kong. And so we went online from the first week in February.

We were also quite haphazard in November. The impact of the protests took the institution by surprise the way the virus has taken the world by surprise. The key challenge we faced then, and I think many other institutions around the world face today, is how to make sure that the teaching quality is not just good for faculty members who are already enthusiastic about virtual and online learning, but for all faculty, even those who thought they would never have to deal with this as part of their teaching experience. But everybody now has to be part of this movement of teaching and learning online.

Sree: You had an advantage because of the crisis and turbulence you faced in November, but was there anything you think universities in America could have done differently?

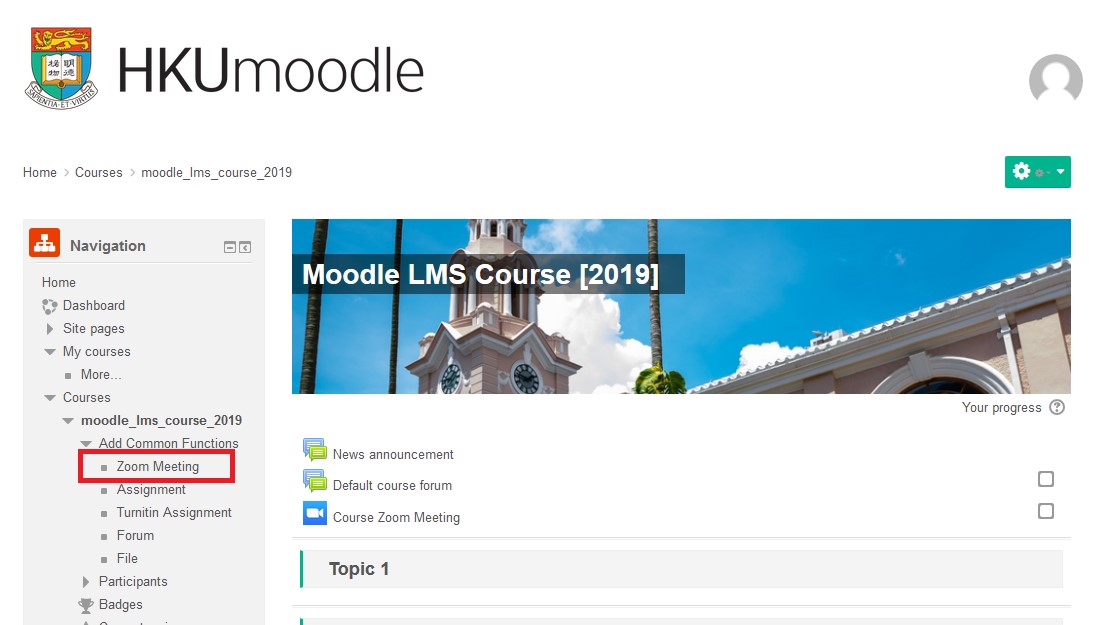

Ian: The key things we’ve done include trying to provide as much support as possible for colleagues and students. From the beginning in November, we had a troubleshooting unit called the Technology Enriched Learning Initiative, whereby colleagues could send a WhatsApp to two phone numbers, manned by actual people who would maybe deal with the query through WhatsApp. If that wasn’t good enough, they could migrate to Zoom, and talk through what they needed to do. We had a live real-time troubleshooting service. We also had webinars and an email system for colleagues and students where inquiries would be answered within a matter of hours. We tried to ensure we had a central organization that could respond to all the queries bubbling up across the campus.

Sree: There is that divide you mentioned, between people who are enthusiastic about digital learning and others who still love a certain way of teaching. I have been a professor for more than 25 years. I think there’s still nothing better than a professor and a classroom of 20 to 25 students all working together and in the same space. But I do see value with digital scale and reach. What is your philosophy of that?

Ian: A great professor who has command of a lecture hall, who has 100 students just waiting for the next sentence…that’s fantastic. We all grew up with that experience. That should be part of the student journey. But alongside that, we’ve learned a lot in these weeks and months from the value of online teaching. I think one of the things we would say in Hong Kong is that we’ve been talking for a long time about flipping classrooms — in other words, posting lectures online beforehand and then saving classroom time for discussion. But we haven’t been doing much of it. We have enthusiasts and they’ve taught us what a great job they’ve done. But I wouldn’t say that the spread has been that great.

Now everybody wants to know, how do you successfully flip a classroom? Broadly, there’s a bit more resistance to speaking in class in Asia than there would be in North America. But some of our teachers are reporting students are more willing to participate in an online tutorial rather than face to face. Some prefer only audio, which is fine. That’s how they’re going to contribute, by making a statement. Some are more comfortable doing that behind the veil of a Zoom tutorial than in a face to face, small class setting.

The key thing is how can we distill all the benefits that institutions in the States, institutions in Asia, and around the world are gaining from online learning. It’s a massive experiment now, whereas before we were doing it in a much more controlled fashion. How do we distill all of the good lessons and keep those, alongside what it was we liked about face to face?

THE HKU EXPERIENCE

Sree: We have a visual to show folks how you were dealing with this. And here is a half-day virtual forum that you showed. Can you talk us through what we’re looking at?

Ian: It’s about the HKU experience the past six months. Many colleagues have been doing a fantastic job with their online teaching and we want to capture that in this four-hour webinar. The first two hours will be on pedagogy and the final two on assessment, which is one of the biggest challenges we face in the move to online. So the forum is just giving teachers a platform to say, “This is what I did, this is what worked for me,” and, “This is what didn’t work for me, this is what I’ve learned from it.”

Sree: Earlier, you used the words “flipped classroom.” Can you explain further what that is?

Ian: The basic concept is that what ordinarily or historically would have been delivered didactically by the professor standing in front of the class…that bit gets flipped. So the professor would record the lecture, put it online, ahead of meeting with students, and then use the classroom session to discuss the material that has been delivered through the online segment of the class.

So rather than spend two hours passively listening to a professor, students do that in their own time before the class and then come onto campus and engage with the professor through that segment of the class. It means that students now have the classroom time to dialogue with the professor about the material rather than just listen to a lecture. So that’s what the flipping concept means.

Sree: That’s something most students and teachers were not used to when they started this. They thought teaching meant just the delivering of a lecture in a class setting. So, trying something new and experimenting is important.

Ian: Yes. Focusing on the active and the interactive, that’s one of the things that comes out of this experiment — how can we capture as much interactive learning as possible? A lot of resources can be planted online. Students are used to going online. They’re used to Google searches, reading Wikipedia, and everything else. That’s how they gain information. What we want to do is to actually engage in dialogue with them and interactive learning with them, and online teaching is enabling us to expand our ways of doing that.

Sree: All right, we have so many questions, we’re going to go for some quick questions and answers. Alejandro asks: “With the radical shift of education online, once the crisis subsides, will there be a significant disruption in higher education learning, a significant shift away from the traditional residential social model to something new, a hybrid perhaps?”

Ian: Yes and no. Many institutions are the kind of classic ocean liner that takes years and decades to maneuver and shift. So, in many respects, they will breathe a sigh of relief and go back to what they’ve always been doing. It’ll still be a battle to ensure all the good things that we’ve done in these months are captured and fed into teaching and learning.

This is not going to go away. In September when Northern Hemisphere universities come back, they’re not going to say, “Campus is back to normal, that was interesting, but we don’t need to do any more of it.” We’re already moving to suspend exchange programs, for instance. And that’s a key part of global exposure for students around the world. Most students in many top institutions expect to have at least one semester of study abroad. And that probably won’t happen in this calendar year.

That means we’re going to try to find ways of putting them together virtually. If you were going to go to an institution in the US or in the UK, let’s see if we can put your classrooms together, at least for a couple of sessions. Let’s see if we can actually put our students together. They can debate issues as two groups of students connected virtually.

Many Hong Kong students come out of high school and go overseas for their undergraduate studies. But there’ll be less of that this year, I think.

A SEPTEMBER HYBRID

Sree: How can teaching and learning quality be assured for next year given that the pandemic still exists or returns, and online learning continues?

Ian: We’re expecting a hybrid when we come back in September. For one thing, students from around the world coming to HKU either to join us as freshmen or as returning students may not be able to travel here then. There could still be quarantine arrangements in place, so even if they got here by late August, they would still have to spend two weeks in quarantine before coming on campus. Chances are we would spend the first few weeks offering classes, both face to face and online.

We also need to be prepared for return waves of the virus next winter, when we may have to go online again at short notice, using lessons we’ve learned this year. We try to set minimum standards and then do better.. The minimum is that colleagues post an annotated PowerPoint or spoken-to PowerPoint. This may be what they would have done in a traditional lecture. So either they do that as a basic form of flipping a classroom, or provide it to students in an annotated form of what they would have spoken about, given as notes.

Instead of delivering a lecture, they make it available to students, and they have a discussion around it so that students are engaging with the material, maybe through a chat box function in Zoom. It’s a way of making a lecture a little bit more interactive. We also enable students to dialogue with teachers. We also have virtual office hours, virtual academic advising sessions, and we encourage use of email and sometimes WhatsApp for colleagues and students to get together.

GAP SEMESTER AND OPEN CAMPUS

Sree: This question is for students who want to come back, but are worried about travel which they nor the university might not be able to control. What do you think about students taking a gap semester?

Ian: We would try to facilitate that, as we have with assessment. For either one or two semesters, we’ve offered three choices in terms of assessment: One is that they retain the letter-grade system; the second is they shift to a pass/fail, because they might not be sure how the standards are going to play; or we allow them to late-drop out of courses. Right up until a week ago, students could late-drop. even though we are only a week from the end of the semester. So they could have taken almost the entire semester, but still late-drop their entire course load and come back next year for free.

That, in effect, means they’ve taken a gap semester this semester, and they will be picking it up again next semester. We want students to have as much choice as possible. They have to take responsibility for how they exercise that choice, but we recognize that there are many challenges in all of this — not only for teachers in going online, but also for students in navigating the online. For some students, it works well. But for others, it doesn’t work so well. So if students want to just drop the entire year, come back next year and do it again for free, then that’s fine with us.

Sree: Professor, did you consider not opening up the campus or did it make sense to just kind of ease things back in the way you have?

Ian: We’ve always had an open campus; dorms have never closed. Students every day for the last six months have been able to come on campus. Given that Hong Kong students tend to live in quite restricted accommodation, with maybe generations of an extended family living in one space that may not have a study area where they can sit quietly, or participate in a Zoom tutorial, we’ve made available spaces on campus: our library and a Learning Commons, for example. We’ve made them as available as possible.

We haven’t gone back online for this final week or two, or back to face to face, other than for essential face to face. One thing we did at the beginning was work out what we simply couldn’t deliver virtually: clinical placements, internships, lab sessions, studio sessions. In the last few weeks, we have brought students in small groups of four at a time.

In January and February, when we were confronting the virus and looking ahead through the semester, we wanted to give students some clarity. What we said was, you will be able to complete your semester online. That meant that students who, for instance, were still in mainland China for Chinese New Year and hadn’t yet come back to Hong Kong, could stay in China and know they would be able to complete this semester. For students in South Asia or in Europe or in North America, they didn’t have to come to Hong Kong either. At that stage, the virus wasn’t known to be in Europe or North America, so for many of our students, they felt the safe option was not to go anywhere near Hong Kong this semester, but to do classes virtually and gain credits.

Sree: How did you keep students safe on campus? Despite all the turmoil in the region, how did you manage to keep them safe and keep those dorms open?

Ian: As I said earlier, the Hong Kong people have been absolutely exemplary. They naturally move into public health crisis mode when something like this flares up. For instance, mask-wearing is not a contested issue here, as it is in the United States and in some other places. Everybody wears a mask when they are on campus and when they’re off campus. We’re still doing that even now that we’re moving to 17 days of zero local transmission. We’re still distancing ourselves socially. We’re still holding as many campus meetings online as well. Most of our meetings take place through Zoom, just as our classes do.

In the dorms, we’re at about one third occupancy in a kind of natural way, because some students didn’t come back. They stayed in mainland China, or in other parts of the world, and obviously, those are the students who would be staying in dorms. We’ve naturally had a lower density in the dorms just by choices that students themselves have made and that has made it easier for us to have social distancing.

GIVING STUDENTS CHOICES

Sree: We have a question from Rosanna, who worries that a transcript filled with pass rather than letter grades would not be competitive. Is this a problem?

Ian: It could be, and that’s what we advise students. We say: we’re giving you these choices. If you opt for pass/fail for an entire semester, or even an entire year, be aware of how that might impact choices you have further down the line. It may mean that if you apply to graduate school in the United States, somebody might look at your transcript and say, “How can you have so many pass grades on your transcript rather than letter grades?”

Even a future employer might look at it and say, “How come, why so much?” Some students have asked whether we could put a footnote on transcripts saying why for this year they could have more pass/fail than letter grades. And I said, we’re not going to do that. You need to take responsibility for these choices. And of course, you can explain it yourself. If an employer in an interview asks about this, you can explain that this was a situation I faced. I wasn’t confident I was navigating the course materials as successfully as I would have on a face to face mode. That could be a very good explanation. But yes, as I said, students have to take the responsibility for how they exercise choices.

LESSONS AND ASSESSMENTS

Sree: Dr. Naoko Kumada from Bard College has a question: Myanmar has 161 confirmed cases and six deaths as of May 4. What can Hong Kong teach neighbors like Myanmar?

Sree: By the way, we should just remind everyone, you are an expert, having written several books based on your research.

Ian: I worry about my friends in Myanmar because the public health situation there is not good. The economic situation is not good. Myanmar has moved into lockdown, but many people can’t afford it. They have to go out and earn a living; otherwise, their families will not survive. Solutions from the developed world are not immediately translatable into the Myanmar context because it doesn’t have the infrastructure, nor the level of economic development to enable it to adopt solutions which have worked elsewhere.

But the basic things that I’ve been talking about in Hong Kong — wearing a mask, washing hands repeatedly, distancing yourself socially, not going into crowded spaces, not using public transport as much as you did — these are the kinds of solutions that can be done in any country in the world. They’re basic and fundamental, and they work.

Sree: Teresa, a lecturer from Hong Kong Baptist University, has a question: what are your views on how to respond to students’ sometimes ansty and disruptive behavior in class when using video conference software

Sree: I might add, we have seen videos of students calling in from bed with their cameras off, or they’re in the dark. And they can be a little angry or upset.

Ian: We don’t insist that cameras be on for Zoom tutorials; we do insist for any assessment. The key is that a student is contributing to the conversation taking place, and they’re doing so on the basis of reading and knowledge and engaging with the material. On the whole, I would say students are doing that at least as well. When we look at attendance in Zoom tutorials, it’s just as good as face to face meetings on campus. When we look at engagement through the Zoom tutorials, we don’t have statistics, but from my colleagues, the broad sense is that there’s just as much participation.

Sree: Here’s a question from Nimisha: How about the financial burden of having to use the internet to study? Not everyone has equal access to the internet.

Ian: That’s an issue for us. Our students come from 100 jurisdictions around the world. We have students in rural China, rural South Asia. Internet speeds are not good. There’s a limit to what we can do, but we do have a financial assistance fund to which students can apply. But it doesn’t make sense for us to give students blanket financial support for internet access, because 90 odd percent of our students don’t need that form of financial support. They have access to high speed internet.

But again, for some students, it’s an issue, when we come to things like assessment. If your internet goes down in the middle of a Zoom tutorial, no problem, but if your internet goes down in the middle of a Zoom exam, that is more of a problem. We’ve had to face that.

Of course, for any student in Hong Kong with such problems, we’ve always kept the campus open, and made learning spaces open to our students. Many have come on campus to make use of these facilities.

Sree: Here is a question from FC Ching: what if the learning experience requires placement/practicum? How can virtual learning help with that? And here are two related questions from Lisa, a HKU lecturer. What is the most pressing concern from faculty members regarding assessment, and what conclusions would you draw about the most effective approach to assessment

Ian: As I said earlier, there are some aspects that can only be done face to face. I mentioned how we’ve reopened our labs and studios on campus. But for off campus work — clinical work, internships with community partners, practicum for, say, social work students that relies on a social setting — it’s not something that we can fully replicate. We have to wait for the society to reopen. We don’t yet know when we will be able to graduate some of our students taking those kinds of programs; the access to social groups and social settings absolutely necessary for their study is not yet available.

The biggest concern about online assessment is cheating. We’re used to having proctored exams in exam halls. We now have online proctoring and I think we’ve got a pretty good system. We didn’t have a very good system in semester one, because we invented that system in two weeks flat, but we’ve now had another few months. We’ve got a system of online proctoring that I’m very confident about, but it hasn’t been fully road-tested yet. That’s our colleagues’ major concern, and then effective assessment on an online basis. We’ve invented our own platform, which we call “OLEX,” which enables colleagues to upload an exam paper and then students to download it and then upload their answers.

Our online proctoring system has very complex protocols. We’ve got training sessions with students with teachers for invigilators (proctors); we will be recording everything both on Panopto and on Zoom, uploading it onto the HKU server; every single student will be monitored through Zoom by an invigilator. These are things we’re trying to do to ensure that our assessment system is credible and that everybody can have confidence in it.

ADDING DIVERSITY TO LEARNING

Sree: Here is a last question, from CF Kwan: does extensive online learning hinder or sharpen people’s communication skills?

Ian: It adds diversity to the learning experience, something they would not otherwise have had. We need to work on this before experiences fade, and while everybody is still in this teaching and learning moment. We need to capture as much of that good diversity as we can. We must be able to have more communication skills for students, because we will be putting them in more diverse situations with more diverse challenges and stimulating them in more diverse ways.

From teachers to people in administrative and managerial positions, the task is to capture what’s been great about this period. There have been problems.

There have been challenges. It hasn’t been entirely smooth. We had a rocky start, but there are benefits and positives in this process and that’s what we need to focus on and make sure it becomes institutionalized and we don’t simply go back to where we were six months ago, as essentially just face to face institutions.

Sree: Thank you so much, professor, for sharing your wisdom, your insights, and your leadership.

Good night from here and good morning in Hong Kong.

Revisit the live show: